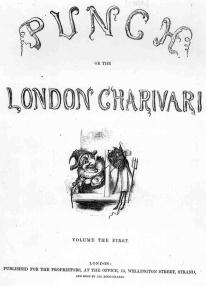

| Punch; or, the London Charivari. |

||||

| vol 1 no 1, 17 Jul 1841 - 08 Apr 1992//. London, Middlesex. Ed: Kenneth Bird (1949 - 1952); Shirley Brooks (assistant editor 1851 - 1870, editor 1870 - 1874); Francis Cowley Burnand (Sir) 1880 - 1906); Alan Coren (1977+); William Davis (1968 - 1977); Bernard Hollowood (1957 - 1968); E.V. Knox (1932 - 1949); Mark Lemon (1841 - 1870); Henry Mayhew (1841 sub-editor); Horace Mayhew (c.1840s sub-editor); Malcolm Muggeridge (1953 - 1957); Owen Seaman (Sir) 1906 - 1932); Tom Taylor (1874 - 1880). Prop: Bradbury and Evans (1842 - 1900+); Bradbury, Agnew and Co (1872+); Stirling Coyne (1841 - 1842); Gilzean-Reid; Ebenezer Landells (1842); Joseph Last (1841); Mark Lemon (1841); Henry Mayhew (1841 - 1842); United Newspapers Group (Ebenezer Landells). Pub: William Bradbury; Bradbury and Agnew; Bradbury and Evans (1841 - 1842, 1846, 1899); Frederick Mullet Evans (1853); Ebenezer Landells (1841 - 1842); Joseph Last (1841 - 1842); Joseph Smith (1870). Printer: William Bradbury; Bradbury and Evans (1841); Bradbury, Agnew and Co (1899); Frederick Mullet Evans (1853); Joseph Smith (1870). Contributors: "Hangman Hanged"; Arthur à Beckett; Gilbert à Beckett (after 1862); F. Anstey (1886); Anthony Armstrong; Matthew Arnold; J. Ashby-Sterry (1860+); Fred Barnard (ill. 1863); "Bab" Beckett (Sir William Schwenck Gilbert); Fougasse Belcher (Fougasse [Cyril Kenneth Bird] ill. 19??); George Belcher (ill.); Charles Henry Bennett (ill.); Alexander Stuart Boyd; Edward Bradley (Rev.) pseud. A.B. or Cuthbert Bede 1847 - 1855); Charles William Brooks (Epicurus Rotundus 1851); Shirley Brooks (1851 - 1870); Thomas Brown (ill.); Robert Browning; Thomas Carlyle; Mortimer Collins; Stirling Coyne; Walter Crane (ill. 1866); Alfred Crowquill (ill.); Jeams de la Pluche; E.M. Delafield; Charles Dickens; Richard Doyle (Dickie 1843 - 1865 ill.); George Louis Palmella Busson du Maurier (ill. 1860 - 1896); Henry Sutherland Edwards (1848); H.F. Ellis; Ainsworth Fletcher; Alfred Henry Forrester; Birket Foster (ill.); Harry Furniss (ill. 1881, 1884); Frederick Gale; John Gilbert (ill. 1843); William S. Gilbert (Sir) ill.); George B. Goddard (1849); Charles Grave (ill. 19??); Paul Gray (ill. 1864 - 1865); Catherine Greenaway (Kate); George Grossmith; Weedon Grossmith (ill.); St. John Hankin; James Hanney; Archibald S. Henning (ill.); Alan Herbert (Sir); Leonard Raven Hill (ill. 1897); Thomas Hood (1843); Leslie G. Illingworth (ill. 19??); Douglas William Jerrold (1841 - 1857); Llewellyn Jewitt (c.1846 - 1849 Manager of Illustrations); Charles Samuel Keene (ill. 1851 - 1890); Graham Laidler (pseud. "Pont" ill. 19??); Ebenezer Landells (ill.); Matthew J. Lawless (ill. 1860 - 1861); John Leech (ill. 1841-1864); Rudolph Chambers Lehmann (1890 - 1917); Percival Leigh (1841 - 1889); E.V. Lucas; Henry William Lucy (Sir) 1897); John MacGregor (c. 1844); Henry Mahew; H. Stacy Marks (ill.); Mary E. Maxwell (Miss Mary Elizabeth Bradden); Phillip W. May (ill. 1895); Augustus Mayhew; Horace Mayhew; Herman C. Merivale; John Everett Millais (Sir) ill. 1863); E.J. Milliken (ill.); A.A. Milne (ill.); George Morrow (ill. 19??); William Newman (ill. 1846); Solomon Pacifico; J. Bernard Partridge (Sir) ill 19??); Watts Phillips; Narcissus Pink (fictional correspondent 1845); George John Pinwell (ill. 1863); Augustus Pugin; Angus B. Reach (1849); E.T. Reed (ill.); Frank Reynolds (ill. 19??); Briton Rwiere; Edward Linley Sambourne (ill. 1867-1881); Owen Seaman; Ernest Shepard (ill. 19??); Frederick J. Shields (ill. 1875); Henry Silver (writer); Albert Smith (1848); Spec; G.L. Stampa (ill. 19??); Joseph Swain (engraver); William Webb Follett Synge; Tom Taylor; John Tenniel (Sir) c.1850 - 1901 ill.); Alfred Tennyson (1846); William Makepeace Thackeray (writer, ill. 1846 - 1847; pseudonyms "Yellowplush", "Fitz-boodle", "Michael Angelo Titmarsh"); Alfred Thompson (ill.); Michael Angelo Titmarsh; Fred Walker (ill. 1869); Artemus Ward; William Henry Wills (1841); Amy Woolner (1859). Names: Cyril Kenneth Bird; George Cruikshank; William Schwenck Gilbert (Sir); Keene (c.1847+); John Ketch; George R. Sims. Size: 28cm, 12pp (1841); 10pp. Price: 2d; 3d (1841-1917); 4d (1846); 4d st (1856); 6d (1917-1948+). Circulation: 5,000; 30,000; 6,000 (no 1, 1841); 40,000/no (1854-1860); 200,000 readers (1860); 7,568; 50,000 - 60,0000 [Miller, John Leech and the Shaping of the Victorian Cartoon, p. VPR 42:3, p. 267]]. Frequency: weekly (Sat 1841,1846). Illustration: cartoon (full-page or smaller 1847); wood engraving (1866); engravings, humourous drawings, pen and ink cartoons, caricatures, sketches. Indexing: index/vol; indexes reprinted separately (Punch Publications); Periodicals Contents Index (1841+); Harden. A Checklist of Contributions by...Thackeray. Departments: politics, fashions, police, reviews, fine arts, music and the drama, sporting, the facetiae (1841); Punch's essence of parliament, notes from the lazy club, attractive theatrical advertisements, a royal academical review (1853); advertisements (1900); novels (serialized), "Author's Misery", drama criticism, cartoons, humour about hunting/housekeepig/cabmen/social climbing/servants/drunkards, abridged novels, commentary, humourous verse, jokes, poetry, reviews. Orientation: liberal (1846); anti-sweatshop (1863). Sources: BUCOP.; DNB ii, 1345-46; NCBEL.; PCI.; Avery, Gillian, with the assistance of Angela Bull, 1965. Nineteenth Century Children: Heroes and Heroines in English Children's Stories, 1780-1900. London, England: Hodder and Stoughton. p.210.; Harris, Beth. “Book Reviews” VPR 33.4 (Winter 2000): 402-415.; Burnand, Francis Cowley. "Mr. Punch: Some Precursors and Competitors". PMM 29 (1903): 96-105, 255-65, 390-8.; Cooper, Dictionary of Contemporaries.; Dunae, Patrick A. "Penny Dreadfuls: Late Nineteenth- Century Boys' Literature and Crime". Victorian Studies 22:2 133-50.; Gifford, Denis. Victorian Comics. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1976.; Gray, Donald A. "A list of Comic Periodicals Published in Great Britain, 1800-1900, with a Prefatory Essay". VPN no 15 (Mar 1972): 2-39.; Harden, Contributions by Thackeray.; Harden, Letters of Thackeray.; Horn, Maurice. The World Encyclopedia of Comics. vol 1. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1976.; Jack, Scottish Newspaper Directory.; James, Louis. Fiction for the Working Man 1830-1850. London: Oxford University Press, 1963.; Layton, Charles and Edwin. Handy Newspaper List, 1912.; Madden, Periodical Press in Britain.; Mitchell's Newspaper Press Directory, 1846, 1847.; Matthews, Poetical Remains. p.200.; Perry, Aldrige. Penguin Book of Comics.; Rayner, William. "Comic Newspapers". N&Q 9:4s (Jun 1872): 479-80.; Repplier, Pursuit of Laughter.; Sutherland Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction.; Uffelman, 1992.; White's The English Literary Journal to 1900.; Williams, Judith Blow. A Guide to the Printed Materials for English Social and Economic History 1750-1850. vol 1. New York: Octagon Books Inc., 1966.; Young, G.M. ed. Early Victorian England. 1934: pp.86-90.; ix, 1164-66; v, 1320-21; vii, 24; x, 786-89, 820-821; xi, 829-32, 877-88; xii, 541-42; xiii, 153-54; xix, 546-55; xvi, 792-93; xxi, 520-21; xxii, 7, 250; xxiii, 4-5, 240-41, 611-12; xxiv, 69-70, 196, 616-617; xxvi.3, 377-8, 463-64, 524-26.; Wynne, Sensation Novel and the Victorian Family.; Henson, Louise, Geoffrey Cantor, Gowan Dawson, Richard Noakes, Sally Shuttleworth, and Jonathan R. Topham, eds. Culture and Science in the Nineteenth-Century Media. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.; Fyfe, Paul. "2008 VanArsdel Prize Graduate Student Essay: The Random Selection of Victorian New Media." VPR vol 42, 2009, p.1-23.; Henson et al. Culture and Science; Varty, Anne. Children and Theatre In Victorian Britain 'All Work, No Play'. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, p.1-250; Moore, Tara. Victorian Christmas in Print. Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, p. 72. Rubery, Matthew. The Novelty of Newspapers: Victorian Fiction after the Invention of the News. Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 64, 86.; Kortsch, Christine Bayles. Dress Culture in Late Victorian Women's Fiction. Farnham: Ashgate, 2009, p.126; Sumpter, Caroline. The Victorian Press and the Fairy Tale. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008; Adams, James, Eli. A History of Victorian Literature. Blackwell Publishing, 2009. Histories: VPR 11:1,p.34; 12:1, pp.15-24; 12:4, p.142; 13:1, pp.64-69; 13:3, pp.103-5; 13:4, p.130; 14:1 pp.33-37; 14:2, p.82; 14:3, pp.102, 132; 15:3, p.88; 15:4, pp.138-42; 16, pp.89, 111, 112; 17:3, pp.94, 115, 117; 18:4, pp.135, 157-9; 19:1, pp.2-16; 19:3, p.115; 19:4, p.139; 20:1, p.31-33; 20:3, p.86, 115; 39:4, pp.410-428; 43:1, p.89-90; 43:2, pp.309-335; Adlard, Owen Seaman.; Adrian, Arthur A. Mard Lemon, First editor of 'Punch'. London and New York: Oxford University Press, 1966. (White 1930, p.153).; Allen, Michelle. "From Cesspool to Sewer: Sanitary Reform and the Rhetoric of Resistance, 1848-1880." Victorian Literature and Culture 30.2 (2002): 383-402.; Altick, Richard D. "Nineteenth-Century English Periodicals." The Newberry Library Bulletin 9 [2s] (May 1952): 255-73.; Altick, Lively Youth of a British Institution.; Altick, English Common Reader.; Baldwin, British Short Story.; Barwin, Bernard "Christmas and Mr. Punch". NR 135 (1950): 495-498).; Basch, Relative Creatures.; Beegan, "Researching Technologies of Printing and Illustration".; Bendiner, Ford Madox Brown.; Blake, "A Visual Apprenticeship".; Bourne, H.R. Fox. English Newspapers. vol 2. New York: Russell & Russell, 1966.; Bowers, Fredson. ed. Studies in Bibliography (vol 25). Z1008.V55. Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia, 1972.; Briggs, Cap and Bell.; Cairns, D. "A recent Scottish literary find." LR 25 (1975): 65-69.; Cantor, Geoffrey and Richard Noakes et al. Science in the Nineteenth-Century Periodical; reading the magazine of nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.; Colby, Cornhill Magazine Under Thackeray: 209-222.; Cooke, Illustrated Periodicals of the 1860s.; Cooter, Cultural Meaning of Science.; Costell, M. "‘Do I never read in the newspapers’: Dicken's last attack on the poor law". DSN 14 (1983): 81-90.; Cranfield, G.A. The Press and Society: From Caxton to Northcliffe London and New York: Longman, 1978.; Cuppleditch, Phil May.; Curtis, Gerard. "Dickens in the Visual Market." Literature in the Marketplace: Nineteenth-century British publishing and reading practices. Eds. John O. Jordan and Robert L. Patten. Cambridge: University Press, 1995: 213-249.; Ellis III, Ted R. "The Dramatist and the Comic Journal in England, 1830-1870". Diss. 29: 2209A Northwestern U, 1968.; Ellis, T. R. "Burlesque dramas in the Victorian comic magazines". VPR 15 (1982): 138-143.; Elwin, Victorian Wallflowers.; Engen, R. "Richard Doyle, master of fairyland: part i". ABMR 10 (1983): 462-463, part ii ABMR 11 (1984): 4-7.; Engen, R. Richard Doyle. Stroud, 1983.; Escott, Masters of English Journalism.; Falconer, “Hundred Years of Punch”.; Foster, "Christmas in the Workhouse".; Foster, “Dolly Varden”.; Foster, "Probing the Workhouse".; Fox, C. "Cruikshank at the Victoria and Albert Museum". BurlingM 116 (1974): 287-8.; Garlick, Barbara, and Margaret Harris, eds. Victorian Journalism: Exotic and Domestic. Essays in Honour of P. D. Edwards. Queensland: Queensland University Press, 1998.; Gates, Leigh Hunt.; Goldman, Taylor, Retrospective Adventures, Forrest Reid.; Habicht, “Shakespeare Celebrations in Times of War”.; Hammond, “Thackeray’s Waterloo”.; Haskins, Fine Art Publishing in Victorian England.; Herd, Harold. The March of Journalism: The Story of the British Press from 1622 to the Present Day. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1952.; Horn, “Theater, Journalism, and Thackeray”.; Horton-Smith, L.G.H. "'Punch': Have You a Complete Set?". N&Q 192 (1947): 36.; Hughes, "Poetry" p.127.; Humphreys, “undiscovered country of the poor”.; James, Fiction for the Working Man.; Janes, "The Role of Visual Appearance in Punch." VPR, 47:1 (Spring 2014):66-86.; Johnson, “Art Public in Punch”.; Jones, Aled. Powers of the Press: Newspapers, Power and the Public in Nineteenth-Century England. England: Scolar Press, 1996.; “Gilbert’s contributions identified”.; Jones, Fleet & Downing.' 1919, 1920.; Kelly, “Punch and the death penalty”.; Knelman, The Murderess and the English Press.; Kooistra, The Illustrated Gift Book and Victorian Visual Culture.; Leary, "Googling the Victorians".; Leary, Punch Brotherhood.; Layard (ed). A Great Punch Editor, 1907.; Ledbetter, Tennyson and Victorian Periodicals.; Maidment, Comedy, Caricature and the Social Order.; Maidment, "Illustration" p.106.; Maidment, B.E. "Ruskin.; Muir, Victorian Illustrated Books.; Nadelhaft, “Punch Among the Aesthetes”; Nicholson, "Remixing the Nineteenth Century Archive".; Nelson, Fatherhood in Victorian Periodicals .; New York: Dover, 1975.; Opyrchal, “Harry Furniss”.; Prager, Arthur. The Mohagany Tree: An Informal History of 'Punch'. New York, 1979.; Price, R.G.G. A History of 'Punch'. London: Collins, 1957 (White 1930, p.154).; Ray, Gordon.; Reed, Victorian Anglo-Catholicism.; Reid, 58 British Artists.; Richardson, Ruth and Robert Thorne. “Architecture.” Victorian Periodicals and Victorian Society. Eds. J. Don Vann and Rosemary T. VanArsdel. Toronto: U Toronto P, 1994: 45-61.; Savory, J. "The Charivari: British Style". Ardn 7: 2 (1980): 5-28.; Savory, J. J. "Robert Browning in ‘Punch’s’ ‘fancy portraits’". SBHC 6 (Fall 1978): 52-53.; Savory, Jerold J. in Sullivan, British Literary Magazines, vol 3, pp.325-329.; Segel, “Thackeray’s journalism”.; Seigel, “Carlyle’s Model Prison”: 81-83.; Shannon, "Colonial Networks and the Periodical Marketplace".; Shapiro, Susan C. "The Mannish New Woman Punch and its Precursors." RES ns 42:168 (1991): 510-22.; Shattock, "Literature and the Expansion of the Press".; Shattock, Joanne and Michael Wolff. eds. The Victorian Periodical Press: Soundings and Samplings. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982.; Sheppard, Cartooning for Suffrage.; Stedman, Classic Victorian and his Theatre .; Sunderland, "Politics for Girls".; Tate, "Satire and Scientific Jargon in Punch".; Unrau, “Pugin in Punch”.; Vranken, "From Copying to Originality in Tit Bits".; White, “Douglas Jerrold”.; Williams, R.W. ed. "A CENTURY OF 'PUNCH'". London: Heinnemann, 1956.; Altick, Richard. Punch; the Lively Youth of a British Institution, 1841-1851. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1997; King, Andrew and John Plunkett. Victorian Print Media: a Reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.; Pearson, “Deconstructing the press”.; Christie, Rechelle. "An Undergraduate American Literature and Identity Course Looks East to Great Britain." Victorian Periodicals Review 39.4 (2006): 429-37.; Codell, Julie. "Imperial Differences and Culture Clashes in Victorian Periodicals' Visuals: The Case of Punch." Victorian Periodicals Review 39.4 (2006): 410-28. Moore, Victorian Chrismas in Print. 59-76.; Ofek, Galia. Representations of Hair in Victorian Literature and Culture. Farnham, England: Ashgate, 2009.; Teukolsky, Rachel. The Literate Eye. Oxford University Press, 2009; McAllister, Annemarie. “Fear and Loathing on the Streets of London: Punch’s Campaign against Italian Organ-Grinders, 1854–1864.” Fear and Loathing: Victorian Xenophobia. Marlene Tromp, Maria Bachman, and Heidi Kaufmann, eds. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2012. pp. 286-311; Horrocks, Jamie. "Asses and Aesthetes." VPR. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 46:1, Spring 2013, pp.1-36; Leary, Patrick. The Punch Brotherhood: Table Talk and Print Culture in Mid-Victorian London. London: The British Library, 2010.; Williams, "British Reportage on the Irish Famine". |

Comments: "This guffawgraph is intended to form a refuge for destitute wit--an asylum for the thousands of orphan jokes--the superannuated Joe Millers--the millions of perishing puns, which are now wandering about without so much as a shelf to rest upon! It is also devoted to the emancipation of the Jew d'esprits all over the world, and the naturalization of those alien Jonathans, whose adherence to the truth has forced them to emigrate from their native land" (Introduction vol 1). Savory: "the weekly Punch has remained in continuous publication as the venerable superstar of English comic periodicals. Shuttleworth et al. call this "undoubtedly one of the most celebrated of all nineteenth-century comic periodicals, if not nineteenth-century periodicals tout court" (59). Leary explains that, "measured by circulation, influence, and longevity-one of the most successful magazines that has ever existed" (Punch Brotherhood 2). "POLITICS-Punch has no party prejudices—he is conservative in his opposition to Fatoccini and political puppets, but a progressive whig in his love of small change. FASHIONS-This department is conducted by Mrs. J. Punch, whose extensive acquaintance with the elite of the areas enables her to furnish the earliest information of the movements of the Fashionable World. POLICE-This portion of the work is under the direction of an experienced nobleman-a regular attendant at the various offices- who, from a strong attachment to Punch, is frequently in a position to supply exclusive reports. REVIEWS-To render this branch of the periodical as perfect as possible, arrangements have been made to secure the critical assistance of John Ketch, Esq., who, from the mildness of the law, and the congenial character of modern literature with his early associations, has been induced to undertake its execution. FINE ARTS-Anxious to do justice to native talent, the criticisms upon Painting, Sculpture, &c., are confided to one of the most popular artists of the day-Punch's own immortal scene- painter. MUSIC AND THE DRAMA-These are amongst the most prominent features of the work. The musical Notices are written by the gentleman who plays the moth-organ, assisted by the professors of the drum and cymbals. Punch himself does the Drama. SPORTING-A Prophet is engaged! He foretells not only the winners of each race, but also the 'vates' and colours of the riders. THE FACETIAE- Are contributed by the members of the following - the court of common council and the zoological society: - the temperance association and the waterproofing company: - the college of physicians and the highgate cemetery:-the dramatic authors' and the mendicity societies: - the beefsteak club and the anti-dry rot company" (Introduction vol 1). "The 'humour of the thing', as admirably exhibited in the solemn burlesques, and the grave travesties, in which it is of a refined character, is well suited to educated minds; and, indeed, though of course there is a great proportion of 'Punch' which is far from the myriada considerable portion has a touch of something above mere vulgar laughter, and is worthy of wise men's perusal" (Mitchell's 1846). "Essays to promote Social Reforms by moral Satire and pungent Ridicule.... [Punch] must not be imagined a mere jester: he mingles satire with his facetiousness and even pathos is blended with his humour: stern truths often come out more strongly in relief and contrast, in a light and laughing form; and the smile of sarcasm gives bitterness to a jest, which might have been wanting in a grave rebuke. Of some follies, again, the reproof must, to be effectual, be as pleasant and piquant as themselves; and emotions of pity are more powerfully (perhaps because more pleasingly) moved, but grief in a grotesque and quaint sort of garb, such as it often assumes in the pages of Punch.... [Punch] is, in a word, 'tragedy-comedy-history-comical- historical-pastoral-tragical historical-tragical comical- historical-pastoral;' and finds its way into the hands alike of the million and the few. One observation may be hazarded as to its readers that, after reading it, they are pretty sure to be in a merry, good-humoured mood. Punch is the mortal enemy of solemn and shallow pretension and false profession, in whatever quarter they may appear; but, as nothing is perfect, it must be confessed, that occasionally both its graphic and literary jokes go beyond the bounds of propriety, and tend to bring into contempt both persons and things we ought to honour and revere" (Mitchell's 1847). Punch has been the most fully studied of British humour magazines.... Introducing the first issue, Mr. Punch announces that he 'has no party prejudices he is conservative in his opposition to Fantoccini and political puppets, but a progressive whig in his love of small change'. In addition to being 'a form of refuge for destitute wit' and 'the asylum for thousands of orphan jokes' and 'perishing puns', the magazine included commentary and cartoons on politics, fashion, fine arts, music, drama, sporting news, and current events.... Through the latter part of the nineteenth century, Punch shifted its emphasis from writing to cartoons, the quality of which helped to retain the magazine's popularity in spite of competition from such rivals as the Tomahawk, the liberal Fun, and the conservative Judy. Punch is the best known British satirical magazine famous also for its illustrations. More expensive than Fun and the Tomahawk, Punch appealed to the middle to upper class" (Ellegard, p.22). "Punch had long been an opponent of sensational literature, particularly of juvenile literature which dignified notorious criminals" (Dunae, p.138). "Thirty years ago I projected Punch as a means of putting an end to the vile satirical papers ... that then formed the staple of light-literature of the weekly press" (quote from Henry Mayhew, in Dunae, p.146). "To understand a Punch cartoon you had to read a caption as long as a short story" (Gifford, Victorian Comics, p.24). "...Punch, by 1884, had settled down to the comfortable, faintly radical, middle-class position it still occupies…the work of Priestman Atkinson in Punch, whose visual puns were a surprisingly hilarious feature of the Late Victorian scene" (Perry, George; p.54). "Destined to play an important role in its country's welfare its cartoons have told history better than historians have told it...It aimed at reproducing exactly the aspects of social and political life at which it mocked...The Christmas of 1843 was approaching when Punch received a poem which seemed eminently unfitted for its cheerful pages, but which...Lemon, was reluctant to let go... The far-reaching effect was to arouse a passion of pity for the underpaid". Hood was said to have written the poem (Repplier, pp.161-2). "...Emperor Wilhelm the Second wrote to Queen Victoria...saying he hoped that she would stop the publication of Punch. He would have hoped it far more ardently could he have foreseen the part that this great weekly would play in the World War...Victoria had no lasting quarrel with Punch; but there were books published in her day...which she would have been glad to suppress had that been one of her prerogatives" (Repplier, p.172). Muir writes: "infallible barometer of English social life...a guide to its costumes and customs...an essential, a representative feature of what England has stood for...Punch has represented, to foreigners and natives alike, the peculiar English sense of humour, the stupidity, the misleading indulgence in understatement, the toleration - of muddle and injustice, as well as of eccentricity and heresy - the willingness to rise in wrath if pushed too far. And all this it has done far more effectively in its pictures than in its letterpress. It was, in fact, the first English periodical to make illustration a regular, and in a very real sense, a principal feature" (Muir, p.100). "The most famous of Victorian comic newspapers....More significant to the magazine's future, the original coterie of contributors under the editorship of Mark Lemon was already in place. Lemon...must take credit for the formula of cartoons and short comic items which made an immediate appeal to the English middle classes....Although fiction (at least long narrative fiction) did not feature in Punch, a number of fiction writers were among the prominent early contributors: Henry Mahew, Douglas Jerrold, Shirley Brooks and, pre-eminently , W. M. Thackeray...(notably in the Snobs of England series, 1847)....After 1874...Punch was a national institution" (Sutherland p.515). On the subject of criminals, Punch writes: "Upon the apprehension of a criminal, we notoriously spare no pains to furnish the nation with his complete biography; employing literary gentlemen, of elegant education and profound knowledge of human nature, to examine his birthplace and parish register, to visit his parents, brothers, uncles, aunts, to procure intelligence of his early school days, diseases which he has passed through, infantile (and more mature) traits of character, etc...we employ artists of eminence to sketch his likeness as he appears at the police court, or views of the farm-house or back kitchen where he has perpetrated the atrocious deed...we entertain intelligence within the prison walls with the male and female turnkeys, gaolers, and other authorities, by whose information we are enabled to describe every act and deed of the prisoner, the state of his health, sleep, and digestion, the changes in his appearance, his conversation, his dress and linen, the letters he writers, and the meals he takes" (quoted in Knelman p.22). "Punch's criticism of what was once called 'rational Dress' (and is now called 'menswear' fashions for women) because this is the most obvious mark of the 'mannish' New Woman of every era, and it is what her more serious, humourless critics have most often seized upon as a sign of her genuine threat to the established social society" (Shapiro, p.510). "In addition to twitting the 'masculinity' of the New Woman in role-reversal fantasies, Punch is also fond of tearing into her seemingly new athleticism" (Shapiro, p.514). "The most common ground for Punch's sniping at the New Woman is that drive for equality of education and affectation of learning which never fails to inflame every satirist, social critic, and insecure male chauvinist" (Shapiro, p.517). "Punch never ceases to delight in poking fun at every female BA in sight, especially those who have earned their degrees with honours, and a chronic source of merriment in its pages are the new women's colleges at Cambridge" (Shapiro, p.518). Richard Noakes in Science in the Nineteenth-Century Periodical notes that "[m]ore has been written about Punch than almost any other periodical, but little attention has been paid to its scientific content" (Noakes, p.93). Noakes himself examines the scientific references and articles found in Punch and notes that "[p]articularly prominent among the 'pure' scientific topics discussed in Punch's first three decades were animal behaviour and development, zoology, astronomy, analytical and industrial chemistry, human development, natural history, and electricity" (Noakes, p.107). Punch was a sister magazine to Once a Week (Hough p.30). The periodical's subtitle acknowledges "its inspiration from France's Le Charivari" (Sheppard, Alice; p.50). "The word cartoon did not assume its modern meaning until...1843, when...Punch...parodied the inept proposals submitted for the new Houses of Parliament frescoes. Soon the term, which previously designated a preliminary artist's sketch or layout, was applied to comical and satirical drawings of similar style and appearance" (Sheppard, Alice; p.39). Punch was full of frightful puns, and it had a social and humanitarian policy (Cranfield, G.A. The Press and Society, p.173). Cranfield writes of Punch, "it regularly denounced harsh sentences for juveniles, flogging in schools and in the army, and the treatment of destitution as a crime" (p.173). However, Punch could also be critical of people who were not British, especially the Irish. Kinealy explains that, during the Famine, Punch and The Times played a key role in shaping public opinion, and that Punch used "satirical articles and caricatures" to criticize how the calamity was handled" (105) and that "the Irish were insufficiently grateful for the assistance which they had received from Britain" (178). Punch even published caricatures of the Irish as ape-like figure who were to be considered along the same social lines as apes and negroes (329; 331). When Punch first came out, the Somerset County Gazette wrote " 'It is the first comic paper we ever saw which was not vulgar. It will provoke many a hearty laugh, but never call a blush to the most delicate cheek' " (Herd, Harold; p.209). However, the sale at first wasn't enough to cover the cost of the paper, so the founders' capital was quickly depleted. The printers, Bradbury and Evans, assumed control of the paper [in 1842], and eventually, it was a great success (Herd, Harold; p.209). Leary calls Bradbury and Evans's acquisition "both the foundation of the magazine's success and the framework-financial and personal-in which it functioned" (Punch Brotherhood 133). Prior to their acquisition, the magazine had struggled to meet the necessary circulation of 10,000 copies. The first number circulated only 6,000 copies (Leary, Punch Brotherhood 140-141). Landells sold Punch to Bradbury & Evans (Altick). During the late 1840s, Punch denounced the primitives and archaistic painters as exemplars of unrealism in art (Bendiner, p.11). Baldwin states the most important quality in an editor or publisher was the ability to "gauge middle class taste." This is most evident in magazines such as Punch where the content had to be "scrupulously clean family entertainment" (27). Punch was a huge success in the satirical genre (Altick 259). Punch published cartoons that suggested "women could go public much more easily than men could go private" (Nelson, Claudia; p.55). Nelson cites articles relating to male-female roles in families. "Certainly Aestheticism was a subject which preoccupied the comic press in the late 1870s and early 1880s; in fact, the development of a burlesque aesthetic vocabulary, iconography, and personality became almost a monomania with Punch and was taken up by Fun and other competitors. Few movements in literature or the fine arts have provoked such a concentrated popular sneer. Nor has parody of literature ever been so closely allied with parody of painting. The personal eccentricities of Rossetti, Whistler, and the young Oscar Wilde; Robert Buchanan's attack on 'The Fleshly School of Poetry'; the unconventional pictures exhibited in the Grosvenor Gallery; Swinburne's alliteration; the merging of art, literature and interior decoration by the younger Pre-Raphaelites - all these and more stimulated philistine comic writers to create caricature 'aesthetics', identified by their unconventional costumes, their long hair, their strange works of art, and especially by their language, archaic, artistic allusive." (Stedman). Burnand describes many periodicals which imitated Punch including: The Puppet Show (1832), Diogenes (1853), Punch and Judy (1869). Uffelman has sixty entries in his handbook with reference to the journal Punch (Uffelman 1992, p.60). Gilbert á Beckett and Henry Mayhew were the founders of Punch (James, p.17). "Leigh, Mayhew, Lemon, and Beckett were on the staff of Punch; Shirley Brooks and Angus B. Reach were not, in this restricted sense, 'Punch Men’” (Burnand, p.265). Brooks became the editor of Punch "on the death of Mr. Mark Lemon, in 1870" (Cooper, Thompson; p.146). According to Burnand, Charles H. Bennett, who began his artistic career by imitating Doyle, was taken onto the staff of Punch as an illustrator after the death of Leech (p.259) Thackeray claimed that Punch paid him "more than double of that [he] g[o]t anywhere else" (Harden p.116). Thackeray became one of the most prominent Victorian authors through Punch, and he had a longstanding relationship with the magazine, particularly Evans. Although he left due to "dissatisfaction with both its politics and its rate of pay, he continued to maintain warmly cordial relations with the firm" (Leary 165). Some contributors to the magazine, such as Sir John Everett Millais, preferred not to appear under their own names (Houfe p.45). Mrs. Caudle, a character in one of [Punch]'s regular cartoons, "created a national furore...[and] set the whole country laughing and talking [with her] nightly matrimonial harangues on the day's domestic events" (Garlick and Harris p.38) in 1845. Arthur à Beckett was turned down for a job with Punch, prompting him to begin other comic or theatre journals such as Glow-Worm and Tomahawk (Garlick and Harris p.78). Punch printed W. S. Gilbert's poem "The Advent of Spring," altered slightly and without a title. It begins with a new first line: "Sing for the garish eye". Punch also published Gilbert's "The Return" and "To My Absent Husband". John Leech, Albert Smith, Percival Leigh and Gilbert à Beckett were collaborators on Punch. After 1841, Leech was the principal artist for Punch, and the country's favourite cartoonist. After illustrator John Leech's death in 1864, Keene produced the paper's "street, field, and railway incidents" while du Maurier handled the "drawingroom swells and affected hostesses" (Houfe p.51). Crane contributed only one drawing to Punch (Reid, Forrest; p.232), while du Maurier contributed thousands (Reid, Forrest; p.179). Gilbert drew for Punch in its early days, the design for the fourth cover in 1843 being his (Reid, Forrest; p.20). Keene also contributed thousands of drawings, and he is considered Punch's greatest artist (Reid, Forrest; p.116). Keene became associated with Punch in 1847 (or shortly thereafter) and remained so until his death. Tenniel became chief illustrator for Punch with the departure of John Leech. Tenniel contributed "Dropping The Pilot" in 1890, a popular cartoon sketch. The contributors of Figaro in London and Punchinello moved to the Punch when it started in 1841 (James, Grant; p.21). "The Snobs Of England” was written and illustrated by Thackeray and serialised from February 1846 - February 1847. Punch serialised "The Story Of A Feather" by Douglas Jerrold. Published "Harry Fludyer At Cambridge", "In Cambridge Courts" and "The Billsbury Election", all by Lehmann. "The Diary of a Nobody" was written by George and Weedon Grossmith and published April 1891 to July 1892 (illustrated by Weedon). Lemon's salary increased from £80 to £1500 per annum, and his contributions gave Punch its distinctive brand of humour. Sir H. W. Lucy contributed Parliamentary sketches signed "Toby, M. P.", which were a "brilliant" feature (Herd, Harold; p.210). Anstey contributed the column "Voces Populi", "shrewdly" illustrated by Partridge. J. Ashby-Sterry was a notable writer of comic pieces. They were often based on his vast and curious knowledge of London and the Thames. Until 1843, Alfred Crowquill shared the pseudonym with his brother, Charles Robert Forrestor. His illustrations particularly influenced the development of Victorian children's books. The influence of George Cruikshank is strongly evident in Punch, although he personally had nothing to do with the magazine. Henning designed the first cover. Burnand wrote a series called "Mokeanna!", which were parodies of the sensational stories in popular journalism of the day. Burnand published the "well-known serial Happy Thoughts in Punch (Cooper, Thompson; p.166). Doyle "severed" his connection with Punch in 1850 because "of its incessant attacks upon his Roman Catholic brethren" (Cooper, Thompson; p.308). Forrester was a writer and an illustrator/artist (Cooper, Thompson; p.376). Wills as "one of the originators" of the publication (Cooper, Thompson; p.970). All or part of Punch's impression was printed on unstamped paper. Any circulation figures represent only those copies stamped for transmission by mail (Jack, Thomas C.). Hood contributed a poem to the Christmas number of Punch (Basch, p.124). "Punch enjoyed high circulation figures despite competition from other illustrated weeklies" (Henson, Louise; p.15). "Punch, 'the mouthpiece of traditional respectability,' often reflected middle-class mainstream attitudes towards women's status, and its impressive plethora of 'hair caricatures,' like its jokes on women's obsession with their dress and looks, confirmed rather than challenged the dominant political and social opinions. Moreover, as Punch was published throughout the mid-to-late Victorian period, its satire registered and articulated growing concerns regarding the changing power relations between the sexes from the 50s to the 90s. As a professional environment, it offered its own satirists a distinctly masculine arts community, a male club which almost amounted to a literary or artistic brotherhood. In light of its exclusive masculinity, it is not surprising to find that many of its caricatures were preoccupied with what was perceived by the 'brotherhood' to be the modern reversal of traditional sexual roles. Punch often trivialized the struggle for the emancipation of women and its accomplishments by portraying its commitment to intellectual and professional pursuits as superficial and whimsical. Its satire dwelt on women's dress and appearance in order to counteract and detract from their serious endeavours." (Ofek, p.212) "Punch's gossip was aimed at artistic circles like that surrounding Rossetti, and concerned their sexual eccentricities or aberrations." (Ofek, p.223) "...Punch relentlessly parodied the art world..." (Teukolsky, p.17). During the Irish Famine, Punch created a fictional character for its Irish correspondent. The character's (pseudo Narcissus Pink) identity remained anonymous so that it could liberally criticize Daniel O'Connell. Location: partial runs: LO/N-1 A vols 24-59 (17 Jul-18 Dec 1841, 18 Jun 1853-02 Jul 1870), QZ/P-1 vol 1 (1841+), XY/N-1 vol 1+ (Jul 1841-Dec 1976); Reprint Editions: microform: Bell and Howell Co., Wooster, Ohio; UMI; N.America: partial runs: ICN (see Altick); LO/N38 A (Jan-Jun); The full text is available on CENGAGE from Gale, Google Books (1854, 1870 and archive.org (1853-1922 imp). |

|||

Reproduced by permission, British Library |

|

|

|

|